Truth and Reconciliation Day, Every Day

Reflection shared by Jody Nelson, Project Lead, Northside Rising

“They try to put sugar in the coffee,” said my 13-year-old son, after a session at school about Truth and Reconciliation. “They don’t want anyone to feel bad.” The lesson was taught by a non-Indigenous woman. Besides the “sweetened” telling of the story of colonization and residential schools, my son witnessed racist remarks from students in the room, which he felt were left unchecked. There are two Mi’kmaw kids in the class. They, unsurprisingly, said nothing. My son is proud of his Metis identity. He has always lived in Nova Scotia, but he longs for the land and people we are from in Northern Alberta. The North is strong in his DNA. How do I teach him to use his proud identity to stand up against these things, these people, these moments? How can I ask him to be the only one in a room full of ignorance and complicity? It’s not that it’s their fault, these children born on the “winning” side of structural divide, but who is accountable if not them? Can we not begin with them?

Hearing this story from my son was a wakeup call for me. How can I expect him to enter bravely into these conversations if I am not? I feel like I have spent decades trying to understand where I fit into the movement towards truth and reconciliation. I was raised by my grandmother, who was a residential school survivor. When the TRC Report came out and the term “residential school” was tossed around the airwaves, it took me a good long while to understand that this was part of my family’s story. My grandma just called it “school”. The stories I heard when I was a child led me to believe that the way she and my aunties and uncles were treated was normal back then. I had to google the list of residential schools to verify that, yes, my family’s experience was part of this revelation by the government of Canada. As if, with the country’s admission, it suddenly became true and wrong in that moment.

Around 40 years ago, my grandma told me stories about the remains of children being found under her school when the building was moved. This is another thing I Googled but found no documentation of. I reach back in my memory, imagining how my grandma came to tell me, an innocent child, about something so horrific. I think she knew, culturally and instinctually, that children need to know the whole truth. Not the “sweetened” story. The truth lives inside of me, but I have struggled to trust its validity. My skin is white, and I do not live on the land I am from. How could my truth be relevant here in Mi’kma’ki?

Imposter syndrome has stopped me from stepping into my cultural identity: self-doubt, feelings of inadequacy, distrust in my credibility, and fear of rejection. So many big questions have stopped me in my tracks: Am I Indigenous “enough” to have a voice? Is my perspective relevant? Maybe I haven’t suffered enough to name the impacts of colonization on my family and on my self? Am I too white, even on the inside? I’ve slowly begun to work at answering these questions for myself.

Throughout my adult life, I have always thought of myself as resilient. I thought I had “done my work”, my inner reconciliation of the opposing parts of how I move through the world. In recent years I have seen the toll of that resilience unfold; I am learning that my resilience is a set of strategies that have kept me safe, and that they do not always serve my whole self. I am starting to recognize this as being rooted in trauma, so much of which points to intergenerational harms that are a part of me – they live in my body, in my story and inform every reaction and choice. They show up like sirens, or earth tremors or sometimes a slithering in my gut, telling me not to trust a situation I am in. This is all wrapped up in my Metis identity. Isn’t it a tragedy, that the journey to cultural awareness and practice starts with acknowledging trauma? It may have started there, but the counterpoint to this is rooted even deeper in me, in my family, and in my culture. It is intergenerational love.

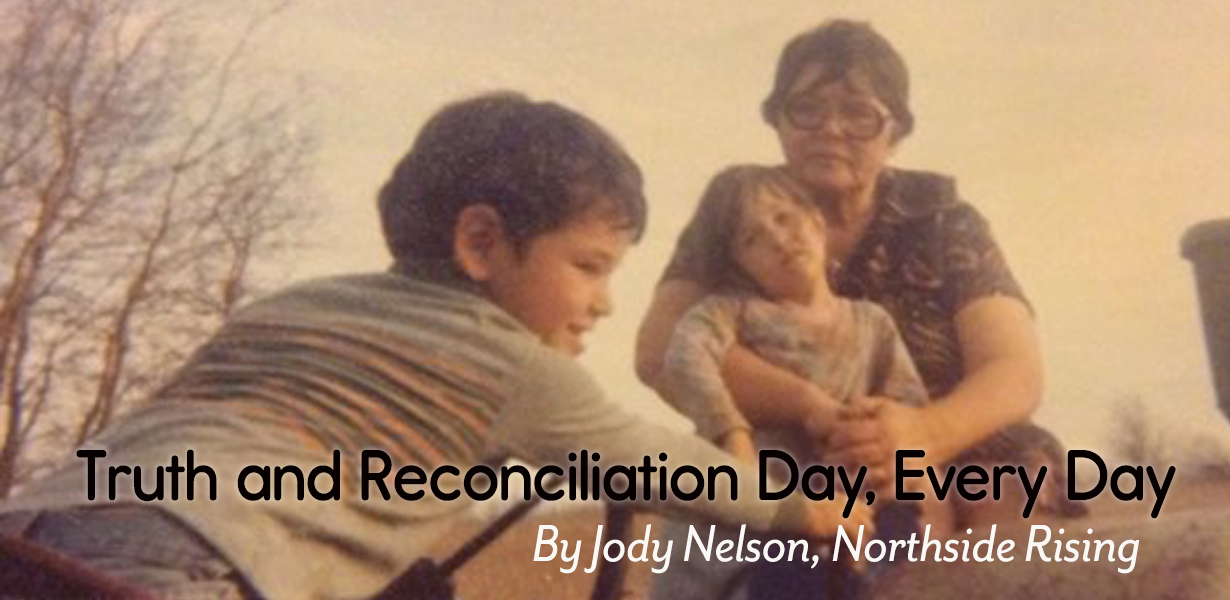

Despite the inconceivable experience of residential school, among many other traumatic events, my grandmother was an incredible woman. She was loving, adaptable, patient, gentle, funny, joyous, and forgiving. She had 8 children, and many grandchildren and great-grandchildren. We were all her world. She cherished watching us grow, making each of us a new pair of moccasins when the old ones wore out, fitted from a tracing of our little feet.

We were dirt poor, living in an old mobile home on a homestead in Little Smoky. In the winters our plumbing would freeze up, so we melted snow in a barrel by the woodstove or used big blocks of ice cut from the pond. When I close my eyes, I can still smell the woodsmoke, tanned hide, and snow melt. I can still feel my grandma’s big, warm arms wrapped around me. We had nothing and everything. We were resourceful. We were generous and accepted generosity. Our home was full of people, and struggle, and love. When I dig beneath the trauma, the self-doubt and the grief, this love is the cornerstone of my resilience and my cultural identity. I have come to know it is as an incredible gift, this childhood filled with the love, stories, and traditions of my Grandma.

This story of love and tradition that runs deeper than my trauma, is the unique voice that I can bring to the movement towards truth and reconciliation. For me that work starts with my children and trickles out into my community and my realm of influence though my work with Inspiring Communities. During the “official” Day(s) of Truth and Reconciliation, I begin to be more intentional about this. Some practices I have started, some are growing and some are evolving:

- I have started adding my Metis identity to work conversations while being open about my self-doubt around this;

- I continue to have deep conversation about identity, responsibility, and accountability with my two boys;

- I continue to learn more – last week my family watched Colonization Road, a documentary on settlement/displacement in Ontario, by Ryan McMahon. I also love his podcast, Red Man Laughing;

- I tracked down my Auntie Hazel’s Bannock Recipe and made them with my kids. We also made a big, hearty stew to go with it…my Grandma would have loved it;

- I am remembering how to do beadwork, learned through countless evenings sitting at the kitchen table next to by grandma;

- I continue to choose this lifestyle here on Hunter’s Mountain: living close to and stewarding this land, growing our own food, giving back to community however we can, and spreading love and compassion.

Share this:

Comments are closed